A Reflection on the Story & an Interview with Jerome Berryman

by Jeannie Babb

The hymn O Come All Ye Faithful is as majestic as it is ubiquitous. For me, it evokes an early childhood memory so visceral that singing the refrain still gives me a shiver.

I’ve sung this Christmas carol in the plain white-walled space of the Southern Baptist Church in which I was raised, and beneath vaulted ceilings, and in a house church with tambourines. Yet, when I hear those words “O come let us adore him,” I am transported back to the seventies.

My sister liked to play records on a child’s turntable that could be packed up like a suitcase. That Christmas season, when I was four or even younger, because we hadn’t yet moved to the new house, she played this song repeatedly. We sang together as we marched round and round the turntable in our little nightgowns with matching robes.

Finally I asked, “What does adore mean?”

She met my gaze, two years older and full of knowledge. “It means kill.”

Let us kill baby Jesus? I froze in horror as my sister relayed how the wise men had told King Herod about Baby Jesus, and the king only wanted to kill him.

Several years passed before I learned the true definition of adore. My sister’s version wasn’t entirely wrong, of course. She was telling me what Herod secretly meant by his deceptive words. Her understanding of hymnody made it plausible that Christians might, every year, put themselves in King Herod’s shoes and sing about the desire to stop the coming revolution by slaughtering a newborn baby — or even every baby in a whole town.

Why tell children these stories at all? Why not stick with a safe cartoon version of Christmas?

Children often hear the more disturbing parts of the Christmas story in songs and liturgy. Leaving these parts out of Christian education means leaving them to someone else to frame and clarify — perhaps an older sibling marching to the music.

Yet is impossible for us to shield children from existential limits in real life, where horrible things do happen. There are adults today who kill children, in Aleppo, in America, and around the world. Sometimes murder seems like an answer. Sometimes, to some people, genocide seems like a solution.

“This is why you don’t leave out the tough parts,” says Godly Play founder Jerome Berryman. “The disturbing elements are very important to the story and need to be included. They give the children a chance to wonder about such things in the safety of the circle.”

The cycle of Godly Play stories includes several ways of telling the Christmas story, beginning with the simple and profound presentation of the The Holy Family each autumn. Most children are exposed to Advent Lessons in four parts. They also experience the birth story within the Faces of Easter. In a story called the The Mystery of Christmas, children hear the fuller account.

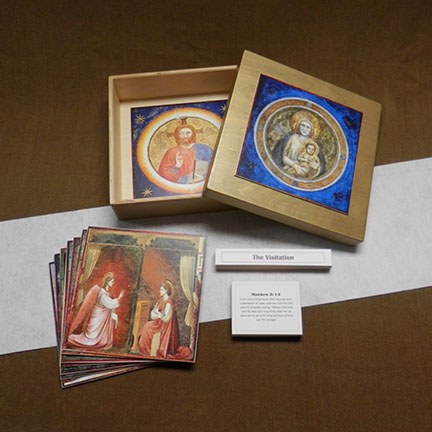

The Mystery of Christmas is a Volume 3 winter extension story based on Giotto di Bondone’s 14th-century frescoes adorning the Scrovegni Chapel in northern Italy and Madeleine L’Engle’s book The Glorious Impossible (Simon & Schuster, 1990). It may be presented before or after Christmas, as time allows. Some programs use it on the feast of Christ the King, and others closer to Epiphany.

This story differs from most Godly Play lessons in a number of ways. First, it differs in appearance. In the Godly Play curriculum, stories that scripture presents as historically rooted are typically rendered in three dimensions. Some of the elements may be flat, but the characters walk upright as they move through the story theater. (Think of the flat wooden People of God standing upright in the sands of the desert.) The Mystery of Christmas depicts Gospel events; yet the story is presented from a gold parable box.

“This is like a parable,” the storyteller says, “but it is bigger than a parable. It is the biggest parable of all, the wonderful impossible. It shows the incarnation, how God became a baby.”

Berryman says the idea of “the biggest parable” began as “an early way of speaking about Jesus discovering that telling parables was not enough. He needed to become a parable.” The same language is picked up in The Greatest Parable, a lesson in Volume 8.

“Aren’t Christmas and Easter parables?” Berryman continues. “The Creator placed the Creator’s image in us on the Sixth Day. The Incarnation and Resurrection do even more. They show God in a human being (the imago dei writ large) so we can see what we are to be like as being in God’s image.”

The story also differs in its inspiration and thus its presentation. Berryman was working with an existing medium: Giotto’s illustrations.

“Have you visited the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua?” he asks. “It is a box, like the Sistine Chapel in Rome, that was transformed by frescos. It is said that Dante watched Giotto at work in the Chapel, but he did not influence him. It was probably the other way around. The way Dante presented scenes in La Commedia shows the sense of a scene displayed in Giotto’s work.”

Like Michelangelo’s frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistene Chapel, this collection of frescoes has been hailed as one of the great masterworks of Christian art. Giotto’s frescos were dedicated in 1305 when the Chapel was consecrated. Berryman says, “This lesson was developed to extend the Christmas story and to introduce children to Giotto’s work.”

L’Engle wrote The Glorious Impossible as a telling of the Gospel based on the Giotto’s frescoes. The genre of her book lies somewhere between a child’s picture story and a coffee table art book. Berryman was inspired to use it in the Godly Play circle.

He says, “I presented this to children for, perhaps, as long as ten years before I turned it over to Godly Play Resources. I had mounted the art on foam core and later asked Resources to develop the material on wood.” Initially churches made their own picture cards by purchasing and cutting up L’Engle’s book. Now The Mystery of Christmas materials can be purchased with completed plaques from Godly Play Resources.

Some would question telling these stories to children at all. Why not keep Christmas light and positive? Yet the world in which children live presents them with many experiences that are neither light nor positive. To see the wonder in the common and find surges of hope in the midst of difficulty, children need stories. Through the exercise of wondering, children learn how to apply past experiences (including vicarious experiences through story) to their own lives.

The process of exploring existential limits is demonstrated in the Mystery of Christmas, perhaps more clearly than elsewhere in the Godly Play curriculum. Children are encouraged to respond to the story — and especially the artwork — as it is encountered.

Berryman says, “The wondering is incorporated in the presentation. This is because the art is 700 years old. It needs some translation.”

On the last Sunday of Advent, I told The Mystery of Christmas to a small group children. Their costumes were hanging in the closet for the Christmas pageant later the same day. Some of the children were still rehearsing their lines in a whisper as they moved into the circle. I wondered how they would respond to the more disturbing elements, especially at a time when they were so steeped in the Christmas story?

I held my breath as I turned the Massacre of the Innocents picture for them to view. “They don’t look like babies,” one of the children said. “They have long legs.”

“They have long legs,” I echoed. “And look at the mothers’ eyes, see how long and narrow they are? The artist tried to make them look very sad.” Turning back to the image of the Adoration of the Magi, I traced the tail of the star. “I wonder if the artist wanted us to remember that it had been two years since the Magi saw the wild star, and the babies were already starting to grow up?”

“This is like something else that happened,” said a child who could not quite remember.

One of the older children sat up straight. “It’s what Pharaoh did! In Egypt!”

I repeated his insight. “It’s what Pharaoh did in Egypt. That’s when Moses was born. I wonder if this baby is like Moses?”

We pondered the question in silence until I reached into the golden box for the last piece:

This was to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet, “Out of Egypt I have called my son.”